By act of the Virginia Legislature, Harrison County was created on July 20, 1784 from parts of Monongalia County. It was named in honor of Benjamin Harrison who graduated from William and Mary College, served in the Virginia General Assembly and Continental Congress, signed the Declaration of Independence, and served as Governor of Virginia from 1781 to 1784. He was also the father of General William H. Harrison, 9th President of the United States, and the great grandfather of Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd President of the United States.

By act of the Virginia Legislature, Harrison County was created on July 20, 1784 from parts of Monongalia County. It was named in honor of Benjamin Harrison who graduated from William and Mary College, served in the Virginia General Assembly and Continental Congress, signed the Declaration of Independence, and served as Governor of Virginia from 1781 to 1784. He was also the father of General William H. Harrison, 9th President of the United States, and the great grandfather of Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd President of the United States.

In 1790, just after Harrison County was formed, it had next to the smallest population (2,080) of the nine counties that were then in existence and fell within the current boundaries of West Virginia. Berkeley County had the largest population (19,713), Randolph County had the smallest population (951), and there were then a total of 55,873 people living within the present state’s boundaries.

The county seat was originally established at the house of George Jackson, at Bush’s Fort on the Buchannon River. The current county seat, Clarksburg, was named for the explorer General George Rogers Clark. John Simpson, ancestor of President and Union Army General Ulysses Simpson Grant, is credited as the town’s first, permanent settler. He arrived in 1765. In 1773, David Davisson claimed 400 acres of land, near present day downtown Clarksburg. The town was chartered by the Virginia General Assembly in October 1785 and was incorporated in 1795. The town’s first newspaper, The By-Stander, began publication in 1810.

Harrison County was the site of numerous battles during the French and Indian Wars (1754-1763), especially around Nutter’s Fort, where Clarksburg now stands, and around West’s Fort, near the present site of Jane Lew. It was also the home of two famous Americans: Confederate General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, and John William Davis, Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1924.

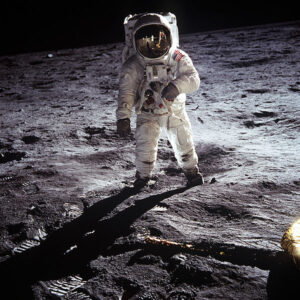

Man Lands on Moon

The Apollo 11 space flight landed the first humans on Earth’s Moon on July 20, 1969. The mission, carried out by the United States, is considered a major accomplishment in human exploration and represented a victory by the U.S. in the Cold War Space Race with the Soviet Union.

Launched from Florida on July 16, the third lunar mission of NASA’s Apollo Program (and the first G-type mission) was crewed by Commander Neil Alden Armstrong, Command Module Pilot Michael Collins, and Lunar Module Pilot Edwin Eugene “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr. On July 20, Armstrong and Aldrin landed in the Sea of Tranquility and became the first humans to walk on the Moon. Their landing craft, Eagle, spent 21 hours and 31 minutes on the lunar surface while Collins orbited above in the command ship, Columbia. The three astronauts returned to Earth with 47.5 pounds (21.55 kilograms) of lunar rocks and landed in the Pacific Ocean on July 24.

Apollo 11 fulfilled U.S. President John F. Kennedy’s goal of reaching the moon before the Soviets by the end of the 1960s, which he had expressed during a 1961 mission statement before the United States Congress: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

Five additional Apollo missions landed on the Moon from 1969–1972.

Battle of Rich Mountain Concludes

In the early days of the war between the states, control of transportation routes through western Virginia was a strategic goal of both Union and Confederate planners.

In the early days of the war between the states, control of transportation routes through western Virginia was a strategic goal of both Union and Confederate planners.

Following their hasty retreat from Philippi in June of 1861, Confederate troops under the command of Col. Robert S. Garnett fortified two key passes. The more southerly of these, Camp Garnett, consisted of earth and log entrenchments overlooking the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike at Rich Mountain, just west of Beverly.

Major General George B. McClellan, charged with securing the loyal counties of western Virginia and protecting the area’s vital B & O railroad for the Union, brought over 5000 troops and 8 cannons to Roaring Creek Flats, about 2 miles west of the Camp Garnett entrenchments.

Confederate Lt. Col. John Pegram was in command of Camp Garnett with about 1,300 men and 4 cannons. He sent a small party to protect his rear at the Joseph Hart homestead at the pass where the Pike crossed the summit of Rich Mountain. On the morning of July 11, the force at the pass consisted of 310 men and one cannon.

Meanwhile in the Union camp, General McClellan was hesitant to make a frontal attack on Camp Garnett Joseph Hart’s 22-year-old son, David, volunteered to lead a flank attack to the summit.

In the early morning of July 11, Brigadier General William S. Rosecrans with almost 2,000 men, set out with young Hart up the mountain. They struggled through the dense woods, delayed by missed directions and drenched by rain.

About 2:30 pm on July 11, the Federal column encountered enemy skirmishers on top of Rich Mountain. The surprised Confederate outpost at the pass took cover behind rocks and trees, and with the help of their one cannon, held off the Federal attack for over two hours. But badly outnumbered, they eventually gave way, and General Rosecrans’ troops took possession of the field.

Colonel Pegram, realizing that the enemy was in his rear, ordered the withdrawal of his remaining forces from Camp Garnett during the night.

On the morning of July 12, 1861, General Rosecrans’ entered the abandoned Camp Garnett from the rear, and sent word to General McClellan that the enemy had been routed. General McClellan promptly sent a telegram to Washington claiming a great victory. This communication secured McClellan’s reputation as a winning general and led to his appointment as commander of the Army of the Potomac.

The Confederates were forced to give up their works at Laurel Hill, and fought a disastrous retreat eastward to Corrick’s Ford and across the Allegheny wilderness. Later, fighting at Cheat Summit prevented any serious Rebel comeback, and battles in the Kanawha Valley claimed even more territory for the Wheeling government. The Federals retained control of most of northwestern Virginia, and except for scattered raids, the Confederacy was banished from the area and its vital railway for the rest of the war.

Two years after the Battle of Rich Mountain, the State of West Virginia was admitted to the Union.

Burr Shoots Hamilton in Duel

In the early morning hours of July 11, 1804, at Weehawken in New Jersey, Vice President Aaron Burr shot and mortally wounded former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton was carried to the home of William Bayard on the Manhattan shore, where he died at 2:00 p.m. the next day.

In the early morning hours of July 11, 1804, at Weehawken in New Jersey, Vice President Aaron Burr shot and mortally wounded former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton was carried to the home of William Bayard on the Manhattan shore, where he died at 2:00 p.m. the next day.

One of the most famous personal conflicts in American history, the Burr–Hamilton duel arose from a long-standing political and personal bitterness that had developed between both men over a course of several years. Tensions reached a bursting point with Hamilton’s journalistic defamation of Burr’s character during the 1804 New York gubernatorial race in which Burr was a candidate. Fought at a time when the practice of dueling was being outlawed in the northern United States, the duel had immense political ramifications. Burr, who survived the duel, would be indicted for murder in both New York and New Jersey (though these charges were either later dismissed or resulted in acquittal), and the harsh criticism and animosity directed toward him would bring about an end to his political career and force him into a self-imposed exile. Further, Hamilton’s death would fatally weaken the fledgling remnants of the Federalist Party which, following the death of George Washington (1732–1799) five years earlier, was left without a strong leader.

The duel was the final skirmish of a long conflict between Democratic-Republicans and Federalists. The conflict began in 1791 when Burr captured a Senate seat from Philip Schuyler, Hamilton’s father-in-law, who would have supported Federalist policies. (Hamilton was Secretary of the Treasury at the time.) When the Electoral College deadlocked in the election of 1800, Hamilton’s maneuvering in the House of Representatives caused Thomas Jefferson to be named President and Burr Vice President. In 1800, the Philadelphia Aurora printed extracts from a pamphlet Hamilton had earlier published, “Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States,” a document highly critical of Adams, which had actually been authored by Hamilton but intended only for private circulation. Some have claimed that Burr leaked the document, but there is no clear evidence for this, nor that Hamilton held him responsible.

When it became clear that Jefferson would drop Burr from his ticket in the 1804 election, the Vice President ran for the governorship of New York instead. Hamilton campaigned viciously against Burr, who was running as an independent, causing him to lose to Morgan Lewis, a Democratic-Republican endorsed by Hamilton.

Both men had been involved in duels in the past. Hamilton had been a principal in 10 shot-less duels prior to his fatal encounter with Burr, including duels with William Gordon (1779), Aedanus Burke (1790), John Francis Mercer (1792–1793), James Nicholson (1795), James Monroe (1797), and Ebenezer Purdy/George Clinton (1804). He also served as a second to John Laurens in a 1779 duel with General Charles Lee and legal client John Auldjo in a 1787 duel with William Pierce. In addition, Hamilton claimed to have had one previous honor dispute with Burr; Burr claimed there were two.

Additionally, Hamilton’s son, Philip, was killed in a November 23, 1801 duel with George I. Eacker initiated after Philip and his friend Richard Price partook in “hooliganish” behavior in Eacker’s box at the Park Theatre. This was in response to a speech, critical of Hamilton, that Eacker had made on July 3, 1801. Philip and his friend both challenged Eacker to duels when he called them “damned rascals.” After Price’s duel (also at Weehawken) resulted in nothing more than four missed shots, Hamilton advised his son to delope, and throw away his fire. However, after both Philip and Eacker stood shotless for a minute after the command “present”, Philip leveled his pistol, causing Eacker to fire, mortally wounding Philip and sending his shot awry. This duel is often cited as having a tremendous psychological impact on Hamilton in the context of the Hamilton-Burr duel.

Happy Birthday America !!

During the American Revolution, the legal separation of the American colonies from Great Britain occurred on July 2, 1776, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence that had been proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. After voting for independence, Congress turned its attention to the Declaration of Independence, a statement explaining this decision, which had been prepared by a Committee of Five, with Thomas Jefferson as its principal author. Congress debated and revised the Declaration, finally approving it on July 4. A day earlier, John Adams had written to his wife Abigail:

During the American Revolution, the legal separation of the American colonies from Great Britain occurred on July 2, 1776, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence that had been proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. After voting for independence, Congress turned its attention to the Declaration of Independence, a statement explaining this decision, which had been prepared by a Committee of Five, with Thomas Jefferson as its principal author. Congress debated and revised the Declaration, finally approving it on July 4. A day earlier, John Adams had written to his wife Abigail:

The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.

Adams’s prediction was off by two days. From the outset, Americans celebrated independence on July 4, the date shown on the much-publicized Declaration of Independence, rather than on July 2, the date the resolution of independence was approved in a closed session of Congress.

Historians have long disputed whether Congress actually signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, even though Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin all later wrote that they had signed it on that day. Most historians have concluded that the Declaration was signed nearly a month after its adoption, on August 2, 1776, and not on July 4 as is commonly believed.

In a remarkable coincidence, both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, the only signers of the Declaration of Independence to later serve as President of the United States, died on the same day: July 4, 1826, which was the 50th anniversary of the Declaration.

West Virginia First to Implement Sales Tax

What two things are sure in life? – Death and Taxes. Fortunately death is at least a little way off for most of us. The idea of sales taxation is not a new idea. The sales tax idea was borne in ancient cultures but is only written in history as having started with Greek emperor Augustus in 9 AD and continuing until 60 AD under Nero. It then disappears until about the 12th century when it reappears in Europe. The first formal laws in Europe were passed in 1292 by France of 1/2% to be collected on the sale of all goods except for food.

What two things are sure in life? – Death and Taxes. Fortunately death is at least a little way off for most of us. The idea of sales taxation is not a new idea. The sales tax idea was borne in ancient cultures but is only written in history as having started with Greek emperor Augustus in 9 AD and continuing until 60 AD under Nero. It then disappears until about the 12th century when it reappears in Europe. The first formal laws in Europe were passed in 1292 by France of 1/2% to be collected on the sale of all goods except for food.

Modern taxation in the United States was first proposed in 1862 during the so-called Civil War as the Union government struggled with finding a way to pay for what appeared to be a long term and expensive conflict. The proposal was for a 1% National tax. The tax bill was tabled and never acted upon. Then in 1921 a national sales tax of 1% was again proposed to help pay for the debt incurred during World War I. Again this measure was defeated, but not before tokens had already been produced. The tokens were supposedly all destroyed.

In 1921 West Virginia was the first state to pass legislation for a sales tax, effective beginning on July 1 of that year. In 1929 Georgia passed similar legislation but neither took the time to figure out how to enforce or implement the system, so there was no progress.

In 1933 eleven states passed legislation for sales tax and by 1940 over 30 states had enacted legislation and systems for sales tax collection due to the success of the early programs at generating revenue for the state.

Remembering the Battle of Gettysburg

On June 24, 1863, General Robert E. Lee led his Confederate Army across the Potomac River and headed towards Pennsylvania. In response to this threat President Lincoln replaced his army commander, General Joseph Hooker, with General George Mead. As Lee’s troops poured into Pennsylvania, Mead led the Union Army north from Washington. Meade’s effort was inadvertently helped by Lee’s cavalry commander, Jeb Stuart, who, instead of reporting Union movements to Lee, had gone off on a raid deep in the Union rear. This action left Lee blind to the Union’s position. When a scout reported the Union approach, Lee ordered his scattered troops to converge west of the small village of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

On June 24, 1863, General Robert E. Lee led his Confederate Army across the Potomac River and headed towards Pennsylvania. In response to this threat President Lincoln replaced his army commander, General Joseph Hooker, with General George Mead. As Lee’s troops poured into Pennsylvania, Mead led the Union Army north from Washington. Meade’s effort was inadvertently helped by Lee’s cavalry commander, Jeb Stuart, who, instead of reporting Union movements to Lee, had gone off on a raid deep in the Union rear. This action left Lee blind to the Union’s position. When a scout reported the Union approach, Lee ordered his scattered troops to converge west of the small village of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

On July 1, some Confederate infantry headed to Gettysburg to seize much-needed shoes and clashed west of town with Union cavalry. The Union commander, recognizing the importance of holding Gettysburg because a dozen roads converged there, fought desperately to hold off the Rebel advance. Other Union troops briefly stopped some Rebels north of town. During heavy fighting, the Confederates drove the Union troops through the streets of Gettysburg to Cemetery Hill south of the town. Lee ordered General Richard Ewell, now commander of the late Stonewall Jackson’s old units, to attack this position “if practicable”, a vague order that Jackson normally took to mean launch an all-out attack. Ewell was not Jackson. He decided not to attack once he saw the Union artillery atop the hill. Had he attacked and succeeded, it might have changed the course of the war.

The rest of the armies arrived that first night. The Union army established a defensive position resembling a fish hook, with Culp’s Hill and the two Round Tops anchoring each end. Lee decided to attack both flanks the next day. On his right flank, Union troops mistakenly shifted out of position, leaving Little Round Top undefended. At the last moment, a Union general rushed troops in just ahead of the charging Confederates. After a long day of fighting, they barely held the position. The misplaced bluecoats were pushed back through The Peach Orchard, The Wheat Field, and Devil’s Den. On the left, Ewell’s assault failed due mainly to his poor leadership.

Thinking the Union center had weakened from these attacks, Lee decided the next day to hit it first with artillery, and then an infantry charge led by George Pickett’s division. Stuart’s late-arriving cavalry was to come in behind the Union center at the same time, but they were held off by Union cavalry led by a young General George Custer. After an hour’s duel, Union artillery deceived the Confederates into thinking their guns were knocked out. Then 13,000 Rebels marched across the field in front of Cemetery Hill, only to have the Union artillery open up on them, followed by deadly Federal infantry firepower. Scarcely half made it back to their own lines. In all, Lee lost more than a third of his men before retreating to Virginia. Meade, a naturally cautious man, decided the loss of one-quarter of his men had been enough, and only feebly tried to pursue Lee, missing an opportunity to crush him.

First Post Office Established in WVa

The first post office in what is now West Virginia was established at Martinsburg on June 30, 1792. Originally built to serve as both a courthouse and post office, the unique turreted red brick and stone building is located on King Street in Berkeley County. It now functions as an art gallery called the Borman Arts Center.

The first post office in what is now West Virginia was established at Martinsburg on June 30, 1792. Originally built to serve as both a courthouse and post office, the unique turreted red brick and stone building is located on King Street in Berkeley County. It now functions as an art gallery called the Borman Arts Center.

Treaty of Versailles Signed

The Treaty of Versailles, signed in the palace’s Hall of Mirrors on June 28, 1918, ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. The date was exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of World War I were dealt with in separate treaties. Although the armistice signed on 11 November 1918 ended the actual fighting, it took six months of negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty.

The Treaty of Versailles, signed in the palace’s Hall of Mirrors on June 28, 1918, ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. The date was exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of World War I were dealt with in separate treaties. Although the armistice signed on 11 November 1918 ended the actual fighting, it took six months of negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty.

Of the many provisions in the treaty, one of the most important and controversial required Germany to accept sole responsibility for causing the war and, under the terms of articles 231–248 (later known as the War Guilt clauses), to disarm, make substantial territorial concessions and pay reparations to certain countries that had formed the Entente powers. The total cost of these reparations was assessed at 132 billion marks (then $31.4 billion, £6.6 billion) in 1921.[ This was a sum that many economists deemed to be excessive because it would have taken Germany until 1988 to pay. The Treaty was undermined by subsequent events starting as early as 1932 and was widely flouted by the mid-1930s.

The result of these competing and sometimes conflicting goals among the victors was compromise that left none contented: Germany was not pacified or conciliated, nor permanently weakened. This would prove to be a factor leading to later conflicts, notably and directly the Second World War.

The Great Textbook War Begins

On June 27, 1974, the school board of Kanawha County met and formally approved new textbooks which many considered to be anti-Christian. About 1,000 anti-textbook protesters demonstrated outside the board office. Despite the protest, the board voted to purchase the books—with the exception of eight of the most controversial high school works. The vote was three to two.

On June 27, 1974, the school board of Kanawha County met and formally approved new textbooks which many considered to be anti-Christian. About 1,000 anti-textbook protesters demonstrated outside the board office. Despite the protest, the board voted to purchase the books—with the exception of eight of the most controversial high school works. The vote was three to two.

Thus began the nation’s most violent protest over public school textbooks. In previous years, the textbook adoption process had been fairly routine, but the atmosphere was different in 1974. The State Board of Education had recently mandated that books used in public schools reflect more multiracial themes. In response, the proposed language arts books featured a diverse range of authors including works by Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg, black rights advocate Eldridge Cleaver, and Sigmund Freud, the father of modern psychiatry. Other books included Animal Farm by George Orwell, The Crucible by Arthur Miller and The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

The textbook supporters generally believed that in an increasingly global society with interconnected economies, students needed to have access to the languages and ideas of diverse cultures. This included an obligation to challenge existing belief systems as well as to question the U.S. government. This concept was especially powerful in 1974, when the Watergate scandal was about to bring down a presidency.

Twenty-seven ministers publicly denounced the books. Ten other ministers and the West Virginia Council of Churches announced support for the books. In general, those who opposed the books were from evangelical churches in rural parts of the county; the ministers who supported the books mostly represented churches located in the city of Charleston, the county seat.

The response was swift. Ministers Ezra Graley, Avis Hill, Charles Quigley and Marvin Horan galvanized the anti-textbook forces and called for a school boycott; 12,000 people signed petitions to keep the books out of schools. The protests were not limited to the religious community. Business leaders began taking sides in the debate too. By late summer, the battle lines were drawn.

On Labor Day, the Rev. Marvin Horan led a rally attended by about 8,000 outraged demonstrators. They labeled their group Concerned Citizens. Horan urged his followers to keep their children out of school until the board reversed its decision.

When schools opened the next day, a large number of students failed to show up. Disputes raged over the numbers. Anti-textbook forces said as many as half the school children in Kanawha County were kept home to protest the books. The school system reported that about 20 percent of students were absent on that first day. Textbook supporters said many students were held out for their own safety, not over objections to the books.

Protesters who opposed the books carried signs and formed picket lines at schools and businesses across the county. One demonstration was at Heck’s Department Store, whose president was pro-book board member Russell Isaacs. One by one, businesses shut down rather than violate picket lines. The protesters even managed to stop Kanawha County’s bus service.

The controversy took a crucial turn on September 4 when some 3,500 coal miners went on strike to protest the textbooks—directly violating orders from the United Mine Workers labor union. The explanation for this unauthorized strike still remains unclear. Some miners simply refused to cross the picket lines that had formed at area mines. Others did not approve of their children reading what they perceived as left-wing books. The miners—experienced in organized demonstrations—helped escalate the protests to another level.

On September 12, in an attempt to calm tensions, the board pulled all the adopted books from schools temporarily and appointed a committee of 18 citizens to review each book. But the compromise failed to satisfy either side. Anti-textbook protesters demanded permanent removal of the books and the firing of school superintendent Kenneth Underwood. Infuriated by what they perceived as censorship, 1,200 students at George Washington High School walked out of school and insisted the books be returned. A leader of the student walkout called Episcopal priest Jim Lewis to ask for assistance. Lewis, a relative newcomer to Charleston, quickly became the most vocal leader of the pro-textbook forces.

That same day, an anti-textbook protestor was shot and wounded. The shooter was wrestled to the ground by demonstrators and beaten severely. After the incident, the county appealed to the state for law enforcement assistance, but Governor Arch Moore was hesitant to dispatch state police to tackle what he considered a local problem. In response, the Kanawha County sheriff announced he could no longer control the increasingly violent situation.

With the community descending into chaos, school superintendent Kenneth Underwood closed the county schools for four days. He said the closing was needed to protect students and employees. Over the next few weeks, the board-appointed citizen committee reviewed all of the books. On September 25, the committee ended up approving the books by an 11-7 margin. Frustrated by the process, the committee’s anti-textbook members split away, conducted their own review, and released a 500-plus-page document that rejected 184 of the adopted books.

The ongoing controversy soon captured the attention of national media. All the major national news outlets—ABC, CBS, and NBC—rushed to Kanawha County to cover the conflict, and the threats and violence continued.

During a rally, the Rev. Charles Quigley prayed for God to kill the three board members who had approved the books. The Ku Klux Klan sent at least three national leaders to Charleston in support of the anti-textbook cause. Protesters attacked a CBS reporter and his film crew, and cars were set on fire. The anti-textbook protestors were threatened too. School board member Alice Moore had to be protected by bodyguards around the clock because of death threats. Gunshots were fired near her house.

Angered by a lack of progress, some of the more radical anti-textbook protesters decided to shut down schools by force. On the night of October 9, 1974, dynamite was thrown through the windows of one elementary school. Another school was firebombed and dynamited. Two nights later, protesters threw Molotov cocktails into a school; another school was firebombed a few nights after that. Then, 15 sticks of dynamite were exploded near a gas meter at the board of education office just after a meeting had adjourned. No injuries resulted from any of these incidents, but the level of violence and destruction shook the community.

On November 8, 1974, the Kanawha County School Board met to determine the final fate of the books. Throughout the controversy, the anti-textbook side complained that public meetings had been held in the small board of education auditorium. Responding to these concerns, the board moved the November 8 meeting to the Charleston Civic Center, which could accommodate thousands of people.

But fewer than 100 people showed up. The recent violence had begun to hurt the anti-textbook cause. Fearing that the meeting would incite more violent behavior, anti-textbook leaders urged their supporters to avoid the Civic Center. Before a sparse crowd, the board voted to return the books to schools.

Although the textbooks had officially been reinstated, the anti-textbook camp was not giving up. The day after the November 8 meeting, they marched again, while their leader, the Rev. Avis Hill, echoed Revolutionary War hero John Paul Jones’s sentiments: “We have just begun to fight.” And the violence continued. In one incident, snipers fired on state police cruisers that were accompanying school buses. In another, a protestor fired a shotgun at a school bus. There were no serious injuries, but the resentment and distrust within the community lingered.

And while the school board vote appeared to be a victory for the pro-textbook forces, the final outcome was not as clear-cut. Conservative school board member Alice Moore introduced a series of guidelines for selecting future textbooks. “Textbooks for use in the classrooms of Kanawha County shall recognize the sanctity of the home,” was one of the guidelines. Also: “Textbooks must encourage loyalty to the United States.” And, “Textbooks must not defame our nation’s founders or misrepresent the ideals and causes for which they struggled and sacrificed.”

The school board approved all of Moore’s guidelines. And in the end, many of the more controversial books approved in 1974 were placed only in school libraries and required a signed parent permission slip to be checked out. Principals were given veto power over individual books. The result was that the most controversial books never entered schools in the rural areas of the county that had objected most stridently.